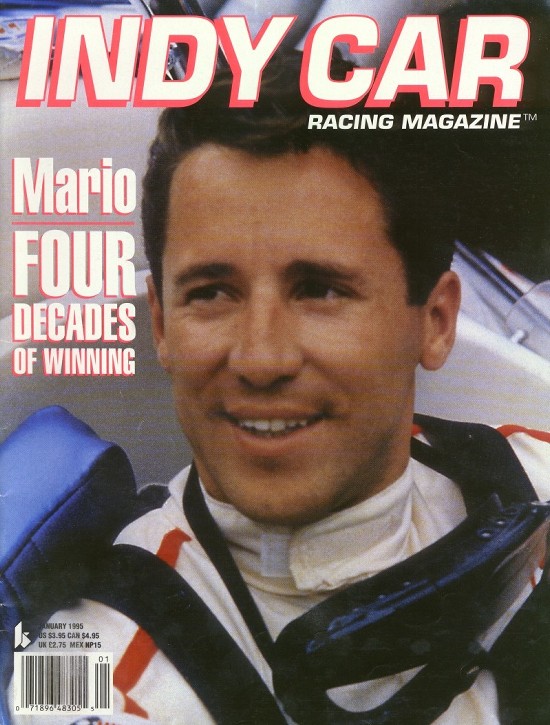

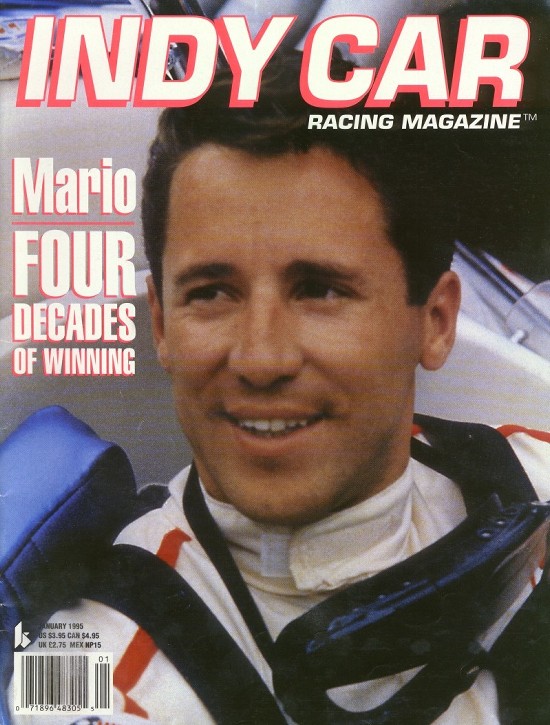

Hinton: Mario Andretti grieving yet again

|

| Mario Andretti saw drivers die in the four decades he was driving, and it does not get any easier |

These are the latest black days in 44 years of losing friends to the sport Mario Andretti still loves unconditionally. And yet, "It's something you never get used to, I can tell you that," the best-known driver ever, in all of auto racing, said Tuesday in a subdued voice. If anything, "It gets worse .."

This was a man grieving yet again, devastated yet again, you could tell on the phone, if you'd known him long enough. Decency forbade asking him to count them all.

"There were too many," he said, at age 71.

First, at Riverside, Calif., in 1967, was Billy Foster — "I would say today he was my closest friend in racing as a driver."

Latest, at Las Vegas this past Sunday, was Dan Wheldon, who had driven for Mario's son Michael in the past and had signed on with the team again for next year.

"No question, it was like losing a family member," Mario said. "It doesn't get any worse than that."

Mario Andretti, quite arguably, has been beleaguered more, longer, by death than any other driver, probably due to the vast diversity of his racing. He won the Daytona 500 in 1967, the Indy 500 in '69 and the Formula One world championship in '78.

The day he clinched the F1 title at Monza, Italy, his Lotus teammate, Ronnie Peterson, was injured, and died late that night. In prototype sports cars, Andretti was a Ferrari teammate of the legendary Pedro Rodriguez, killed in Germany in 1972.

There have been few drivers at the higher levels that Andretti didn't know, and "Nothing is ever the same after you lose a buddy, someone who has touched your life," he said Tuesday.

I sat with him in 1991 at Michael's home, reviewing video of the fatal crash of the humble journeyman NASCAR driver J. D. McDuffie, listening to his outrage at the shortcomings of safety measures at Watkins Glen, N.Y.

We talked at length at the funeral of Davey Allison, who died of injuries suffered in a helicopter crash into the Talladega infield in 1993.

At Homestead, Fla., after promising young Canadian Greg Moore had been killed in a CART race at Fontana, Calif., I heard the outrage again, this anger about a grassy area that allowed Moore's car to skate wildly, flip, roll, and disintegrate. It should have been paved, Mario said.

"They want pretty green grass for the TV shots? Well, then paint the goddamned asphalt green," he growled.

Suffice it to say Mario Andretti never has pulled a punch when he thought there were shortcomings in safety measures.

So he of all experts was credible when he said on Tuesday that this time, Sunday, "The safety aspect worked tremendously, it worked very well, except for one guy. You look at the replays over and over, and there were hard impacts, cars flying all over the place, and Dan was the only real unlucky one, to be flying closer to the wall, and he got into the catch-fencing.

"If he would have got into the SAFER barrier [just below the fence], he would have been brushing himself off and have a cup of coffee later. Look at how hard some of those [other] guys hit, and the worst thing you had was like a broken finger."

Andretti does have a procedural criticism. INDYCAR rules strictly dictate uniform technology in the cars, for parity.

"All along I was somewhat concerned about the fact that the cars are so equally matched by a spec series, and so when they're running on these ovals they can't get away from one another.

"They're inches apart for a couple of hours at tremendous speeds, and the slightest miscalculation can spell disaster.

"Vegas is a beautiful facility, it's perfect in many ways. That makes it too easy for these cars, which have great potential cornering speed, to be three abreast or even four abreast through the corners. As you know, the slightest miscue is what caused it all, and it becomes a chain reaction because they're all together."

INDYCAR has drawn wide criticism for starting 34 cars Sunday, more cars on a 1.5-mile track than the 33 in the Indy 500 at 2.5-mile Indianapolis Motor Speedway.

"Obviously, the more cars, the more of a chance for something like this to happen," Andretti said. "At the same time, you want a spectacle. What makes NASCAR a spectacle on the ovals? You've got 43 cars. Maybe it would be nice for us to have that many cars, but then you've got three times the danger aspect.

"Here, if you'd had 26 cars [a more common field for IndyCar], would that have made a difference? I don't know … the other part is, to fill a field like that [34], you don't have all experienced drivers. But we've all been inexperienced. How do you gain experience? You gotta be doing it the first time sometime."

No matter the science applied to safety, "I don't think we'll ever be 100 percent safe. Like you're not 100 percent safe when you drive to work. Or, unfortunately, when you're flying.

"But the sport has come a long way."

So this really was a matter of bad luck more than anything left undone by the organization?

"Yeah. I feel very strongly about that. Because if you look at this thing realistically, you examine exactly what happened, that [luck] is what it is. He was dealt a bad card on that round. But for a couple of inches he probably would have been all right."

Open-cockpit cars invite what biomechanical engineers call injuries of intrusion — that is, foreign objects can get into the car with the driver. Wheldon likely would have survived with some sort of roof over his head.

But to do that, "They might as well have a stock car," Andretti said. "This is the purest form of the sport. This is the way it was born, and it's been running like this for over 100 years. But I think, quite honestly, the cockpit protection is adequate.

"I think what really caused this was the cars being launched. The cars becoming airborne. And if you look at the design of the 2012 car, that very aspect was dealt with."

In open-wheel racing, when the tires of one car come in contact with those of another, "that's a launching pad," Andretti said. "The new car eliminates this flying, by having the rear wheels partly enclosed. At least we've got that to look forward to.

"But we got unlucky on this very last one," this very last IndyCar race featuring completely open wheels. "We had the so-called 'big one.' Like in NASCAR, they talk about the big one at Talladega and Daytona. But at least they have fenders. It's bad enough for them … "

In recent decades, every fatality at the major levels has brought change, "after the horse is out of the barn," as Johnny Rutherford used to put it. This time, INDYCAR was already at the brink of making the change from completely exposed tires that caused, or at least exacerbated, Sunday's melee.

Still it is one race too late.

And now Mario Andretti is left to mourn yet another of so many friends dead.

At least nowadays the dying is less frequent, what with all the safety science.

"Back in the '50s, '60s and '70s, it was not even cool for a driver to ask for more protection," Andretti remembered.

"Billy Foster was killed just in front of me, before I was ready to go qualify at Riverside. I was the next guy to go out to qualify and my best friend got killed.

"Those are tough ones. … There were too many. And it gets worse … " Ed Hinton on ESPN.com